Multicast is one of those topics I have been meaning to learn properly for a long time. When I did my JNCIS-ENT about eight years ago, I studied multicast, but I honestly do not remember much of it now.

I recently started doing some revision and decided to write a series of blog posts as I go through it again. I want something I can come back to in the future without having to relearn everything from scratch. Hopefully, as a reader, you will also find it useful and easy to follow. If you want to learn multicast, I am going to assume you are already familiar with unicast and broadcast.

As always, if you find this post helpful, press the ‘clap’ button. It means a lot to me and helps me know you enjoy this type of content.

Unicast

Unicast is the most common method of IP communication. It is simply a one-to-one conversation between two devices. One device sends traffic, and one specific device receives it. Most of what we do on a network every day is unicast. For a simple example, think about opening a website from your laptop. Your laptop sends traffic directly to the web server hosting that site, and the server sends the response directly back to your laptop. No other devices receive that traffic, and no other devices are involved in the conversation. Unicast works well for most use cases, but as you will see later, it is not always the most efficient option when the same data needs to be sent to many receivers.

Broadcast

With broadcast, a sender sends traffic to every device on the local network/segment, whether they want it or not. There is no selection and no filtering. If a device is on that broadcast domain, it will receive the traffic.

A common example is ARP. When a device wants to find the MAC address for an IP on the local network, it sends a broadcast asking who that IP has. Every device sees the request, but only the device with the matching IP responds. It is also important to remember that broadcast traffic is limited to the local network segment. Routers do not forward broadcasts to other segments, so broadcasts never cross a routed boundary.

Multicast

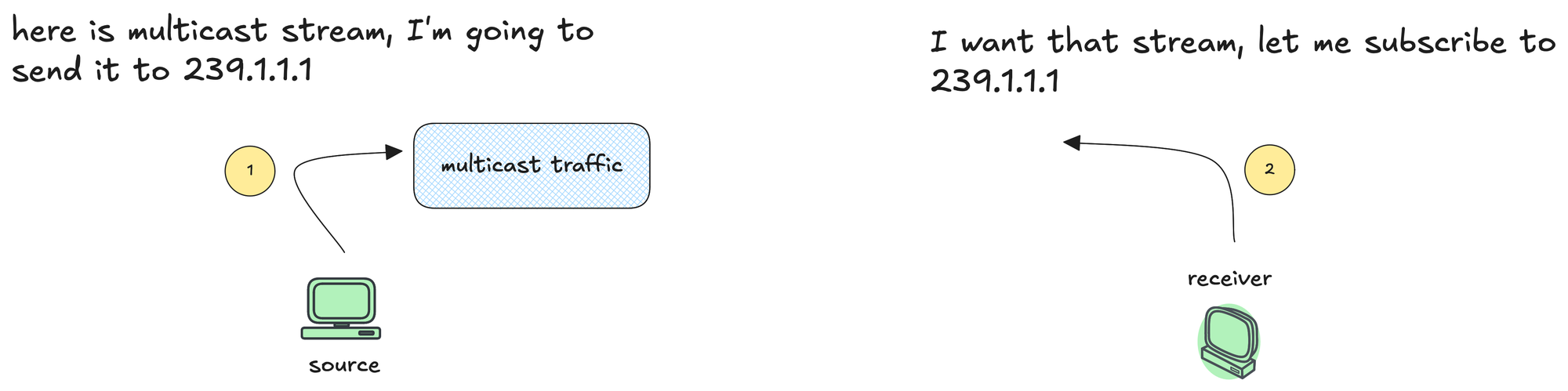

With multicast, the source sends only a single copy of the traffic into the network. As that traffic moves through the network, it is replicated along the path, but only where there are interested receivers. This means the sender does not need to send multiple streams. The multicast-enabled network manages the duplication, and only devices that have joined the multicast group will receive the traffic. Unlike broadcast, multicast is not limited to the local network segment. Multicast traffic can be forwarded by routers and can reach receivers across different subnets. The key difference is that not every device will receive the traffic. Only devices that have joined a specific multicast group should get the data.

A good way to think about multicast is like a radio station. The sender transmits a single copy of the channel, and any device that wants to listen can tune in to that frequency.

To make this work, the network needs some extra logic. Routers need a way to learn which multicast groups exist and where interested receivers are located so they can forward traffic only where it is needed. At the same time, within a local segment, switches need a way to understand which ports have receivers that want to receive a specific multicast stream.

This means multicast relies on several different protocols working together. Some operate between routers (PIM), and others operate within a local network segment (IGMP). Over the next few posts, I will walk through these protocols and explain how they fit together to make multicast work in a controlled and predictable way.

In this diagram, the routers in the path should only forward the stream if there are interested receivers downstream. If no one has joined the multicast group on a given path, the routers should not send traffic that way.

The same idea applies to the local segment. The switch should only forward multicast traffic out of ports where receivers have shown interest in that group. Ports with no interested devices should not receive the multicast traffic at all.

How are Unicast and Broadcast Traffic Forwarded?

For unicast traffic, routers look at the destination IP address in the IP header and do a routing table lookup. Based on that lookup, the packet is forwarded out of an interface toward the destination. Every hop repeats this process until the packet reaches the final receiver.

Switches work at Layer 2 and make forwarding decisions based on the MAC addresses. Every Ethernet frame has a source MAC and a destination MAC, and the switch uses this information to decide where to send the frame. For unicast traffic, the switch looks up the destination MAC address in its MAC address table and forwards the frame out of a single port. If the destination MAC is not yet known, the switch floods the frame until it learns where that device is located.

Broadcast traffic uses a special destination MAC address of FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF. This address is all ones in binary, which in binary looks like 11111111 repeated six times. When a switch sees this destination MAC address, it knows the frame is a broadcast and floods it out of all ports in the same VLAN, except the port it was received on. This behaviour ensures every device on the local segment receives the broadcast frame.

Multicast Addressing

As multicast traffic moves through the network, routers and switches need a way to identify it and treat it differently from unicast and broadcast traffic. Routers do this by looking at the destination IP address (multicast group address) in the IP packet. If the destination IP falls within the multicast range, the router can immediately tell that this is multicast traffic.

Switches look at the Ethernet frame, specifically the destination MAC address. Multicast frames use a special range of MAC addresses (more on this later), which allows the switch to recognize that the traffic is multicast.

Other than these destination addresses, a multicast packet is no different from a unicast packet. The headers are the same, the source IP is still a unicast address. The only real difference is that the destination IP is a multicast address and the destination MAC is a multicast MAC address.

Multicast Class D IP Addresses

- Multicast IP addresses come from Class D

224.0.0.0/4, which ranges from224.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255 - That's about 268 million (2^28) IP addresses.

- These addresses are not assigned to individual devices. Instead, they represent multicast groups that receivers can choose to join.

- Class D addressing is considered a flat address space. There is no concept of subnetting or network and host portions. Each multicast IP address simply represents a group.

When traffic is sent to a Class D address, it is delivered to all devices that have joined that multicast group. Devices that have not joined the group will not receive the traffic, even though it is sent to a shared address.

So far, I have been using the term multicast group, but it is worth being clear about what that actually means. A multicast group is simply an IP address from the Class D range that represents a stream of traffic. When a receiver wants to receive that traffic, it joins the multicast group. When it no longer needs the traffic, it leaves the group.

Multicast Class D Reserved Addresses

- 224.0.0.0 to 224.0.0.255 - Reserved for local network control traffic. These addresses are used by routing and control protocols and are never forwarded by routers beyond the local segment. If you remember from OSPF, it uses the multicast IP addresses 224.0.0.5 for all OSPF routers and 224.0.0.6 for OSPF designated routers

- 232.0.0.0 to 232.255.255.255 - Reserved for Source Specific Multicast (SSM).

- 239.0.0.0 to 239.255.255.255 - These addresses are meant to be used inside an organization and are not expected to be routed on the public internet. I think of this as the RFC1918 range.

Multicast Mac Addresses

As we covered earlier, multicast traffic uses a destination IP address from the Class D range. When a host wants to receive this traffic, it joins the multicast group (don't worry, we will cover this in detail later). If we look at a single packet from a multicast stream, the source IP will be the unicast IP address of the sender. The destination IP might be something like 239.1.1.1, which represents the multicast group.

At Layer 2, the destination MAC address is not the burned-in MAC address of a receiving host, because there is no single receiver in multicast. Multiple hosts can receive the same stream, and the sender does not know who or how many they are. Instead, the destination MAC is a multicast MAC address derived from the multicast IP. For IPv4 multicast, this MAC address starts with 01:00:5E.

This is different from unicast traffic. With unicast, the destination MAC is either the MAC address of the receiving host if it is on the same subnet, or the MAC address of the next-hop router. With multicast, there is no single receiving host, so the frame is addressed to a multicast MAC that represents the group, not an individual device.

Multicast MAC OUI and Mapping

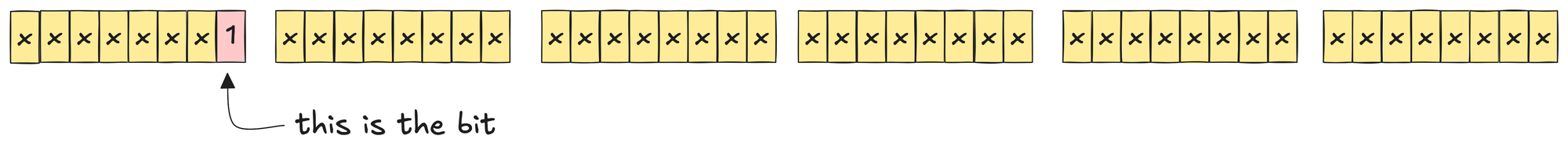

The prefix 01:00:5E is the Organizationally Unique Identifier, or OUI, used for IPv4 multicast MAC addresses. Within a MAC address, the least significant bit of the first octet (right-most bit of the first octet) indicates whether the frame is unicast or multicast. This bit is called the I/G bit, short for Individual or Group.

- If this bit is set to 0, the MAC address is unicast.

- If the bit is set to 1, the MAC address is multicast and represents a group.

In hexadecimal, the first byte of a multicast MAC address is 01. When you convert this to binary, it becomes 00000001. Reading from left to right, the least significant bit is set to 1, which means this is a multicast address/group.

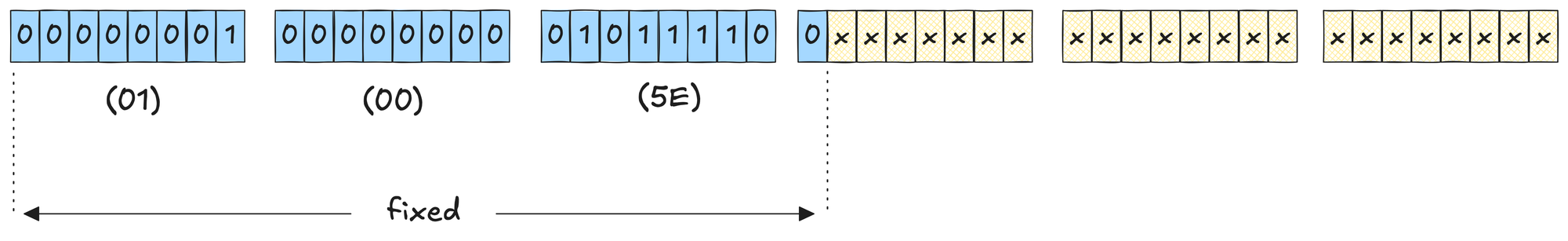

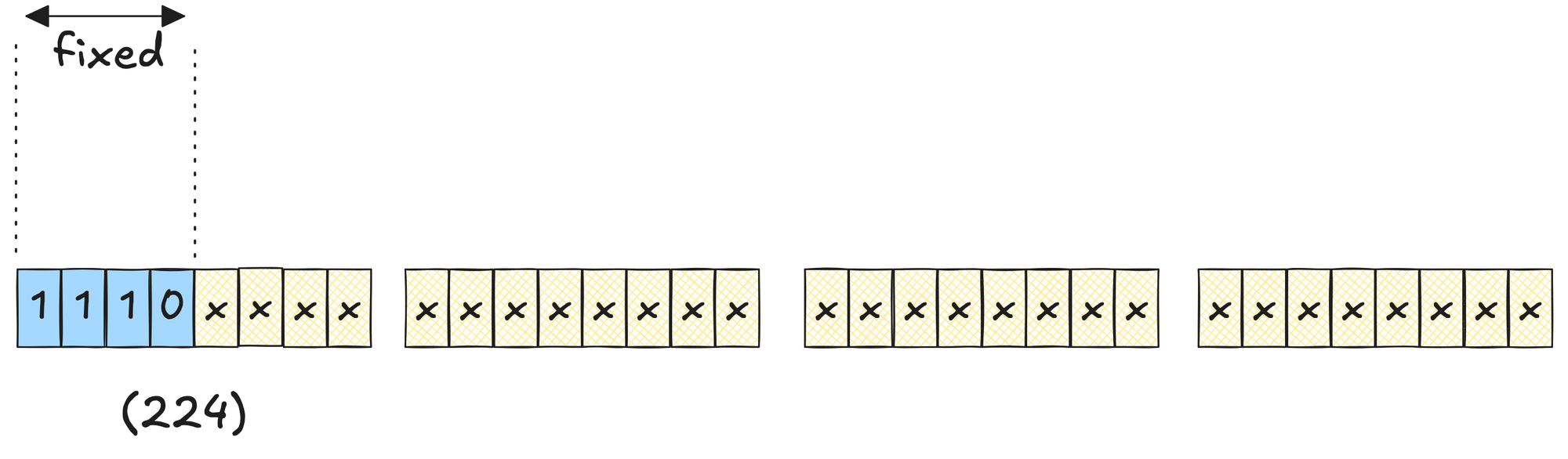

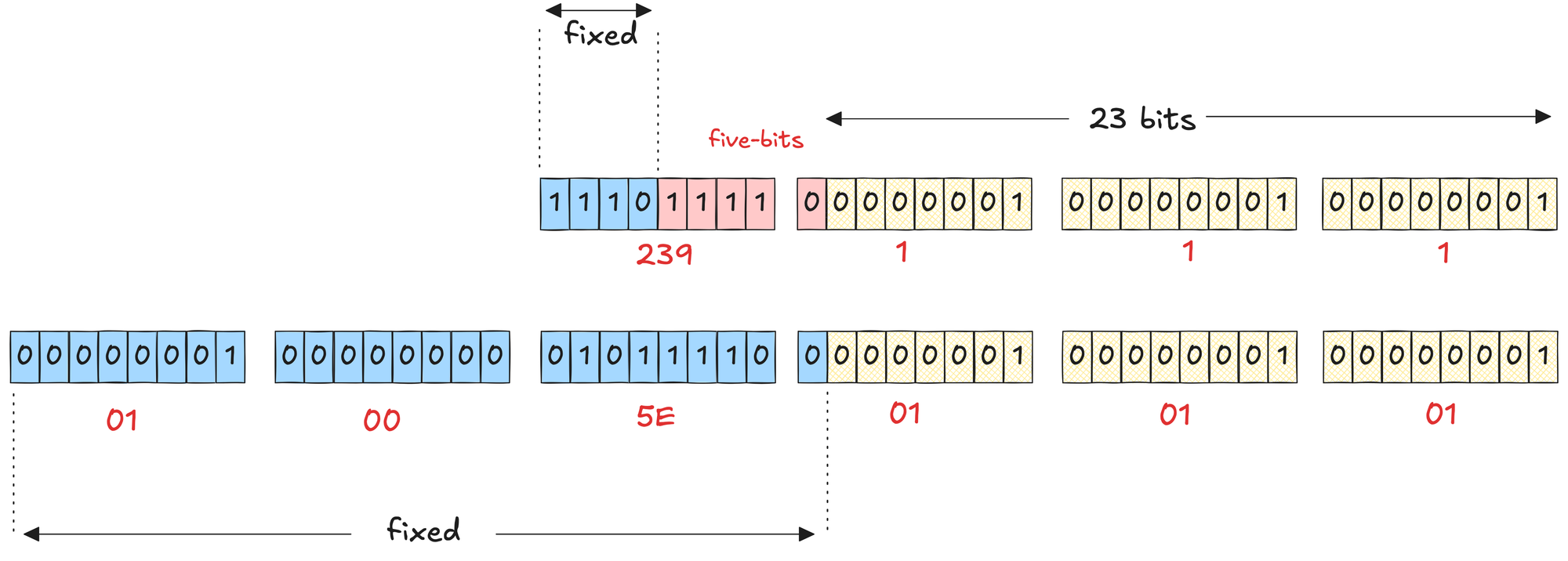

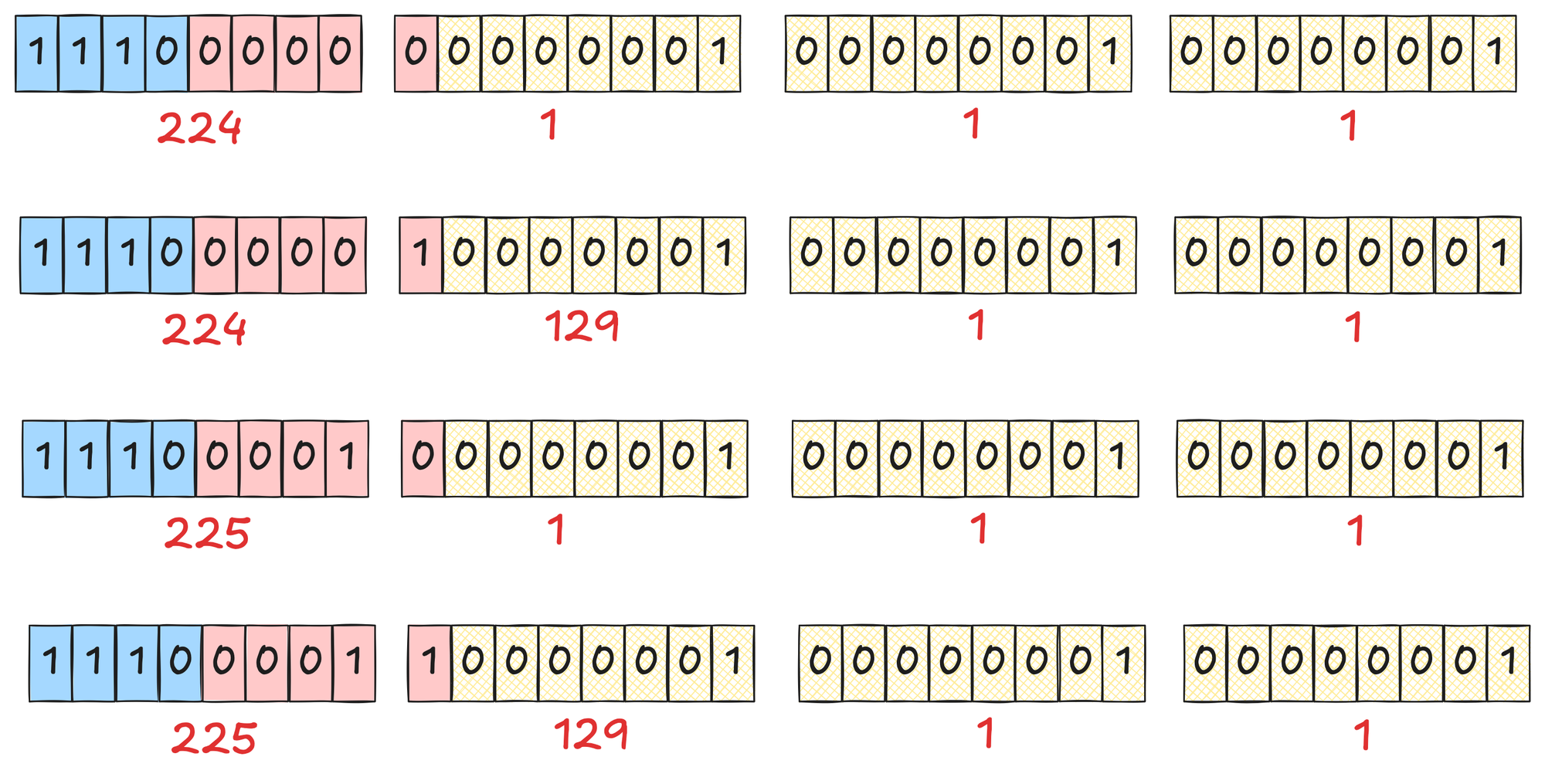

A MAC address is 48 bits in total, the first 24 bits are fixed to 01:00:5E. That leaves 24 bits at the end of the MAC address. However, the most significant bit of those 24 bits is also fixed to 0. Because of that, we are left with only 23 bits that can actually be used for mapping multicast IP addresses. This gives us 2²³ possible multicast MAC addresses.

Now look at the IP side. Multicast IP addresses are Class D, which means the first 4 bits are fixed to 1110. That leaves 28 bits that can vary, giving us 2²⁸ possible multicast IP addresses.

This is where the mismatch appears. We have 2²⁸ multicast IP addresses that need to be mapped into only 2²³ multicast MAC addresses. The difference is 2⁵, which means 32 different multicast IP addresses will map to the same multicast MAC address.

In binary terms, this happens because only the lower 23 bits of the multicast IP address are copied into the MAC address. The upper 5 bits of the IP address are ignored during the mapping process. If those upper 5 bits change, but the lower 23 bits stay the same, the resulting multicast MAC address will be identical.

MAC Address Mapping Example

Let's look at an example with the multicast IP of 239.1.1.1. We can write this in binary as 11101111 00000001 00000001 00000001 If you look at the figure below, we know we can only copy the last 23 bits of the multicast IP into the multicast MAC address. For 239.1.1.1, the multicast MAC address becomes 01:00:5E:01:01:01

Now, we can change the five bits shown in red (the bits that get ignored), and the MAC address will not change. For example, if I change the last of those five bits, which is the rightmost bit in the second octet, the IP becomes 239.129.1.1, but the MAC stays the same. 239.129.1.1 in binary is 11101111 10000001 00000001 00000001

So, a single multicast MAC address of 01:00:5E:01:01:01 actually maps to 32 different multicast IP addresses. This happens because the five bits of the multicast IP address are ignored during the MAC mapping. As long as the lower 23 bits stay the same, the resulting MAC address will be identical.

We can play around with those five bits. If I set all five bits to zero, the address becomes 224.1.1.1. If I then flip the first bit of the second octet to 1, it becomes 224.129.1.1, and so on.

By changing only those five bits, you can make 32 unique combinations, which gives you 32 different multicast IP addresses that all map to the same multicast MAC address.

224.1.1.1

224.129.1.1

225.1.1.1

225.129.1.1

226.1.1.1

226.129.1.1

...

...

237.1.1.1

237.129.1.1

238.1.1.1

238.129.1.1

239.1.1.1

239.129.1.1Similarly, if we look at the multicast IP 224.10.10.10, it maps to the multicast MAC address 01:00:5E:0A:0A:0A. All of the following multicast IP addresses will map to this same MAC address.

224.10.10.10

224.138.10.10

225.10.10.10

225.138.10.10

...

...

239.10.10.10

239.138.10.10Here is an interesting story I came across in this video. When Steve Deering was working on multicast back in 1989, an OUI cost around $1000. He worked out that he would need 16 OUIs to achieve a one-to-one mapping between multicast IP addresses and MAC addresses.

The organization he was working for could only afford (or decided) to buy a single OUI. Even then, that OUI was split in half, and only one half was allocated to Steve for multicast use. That limitation is what led to this mapping madness.

Multicast Forwarding Overview

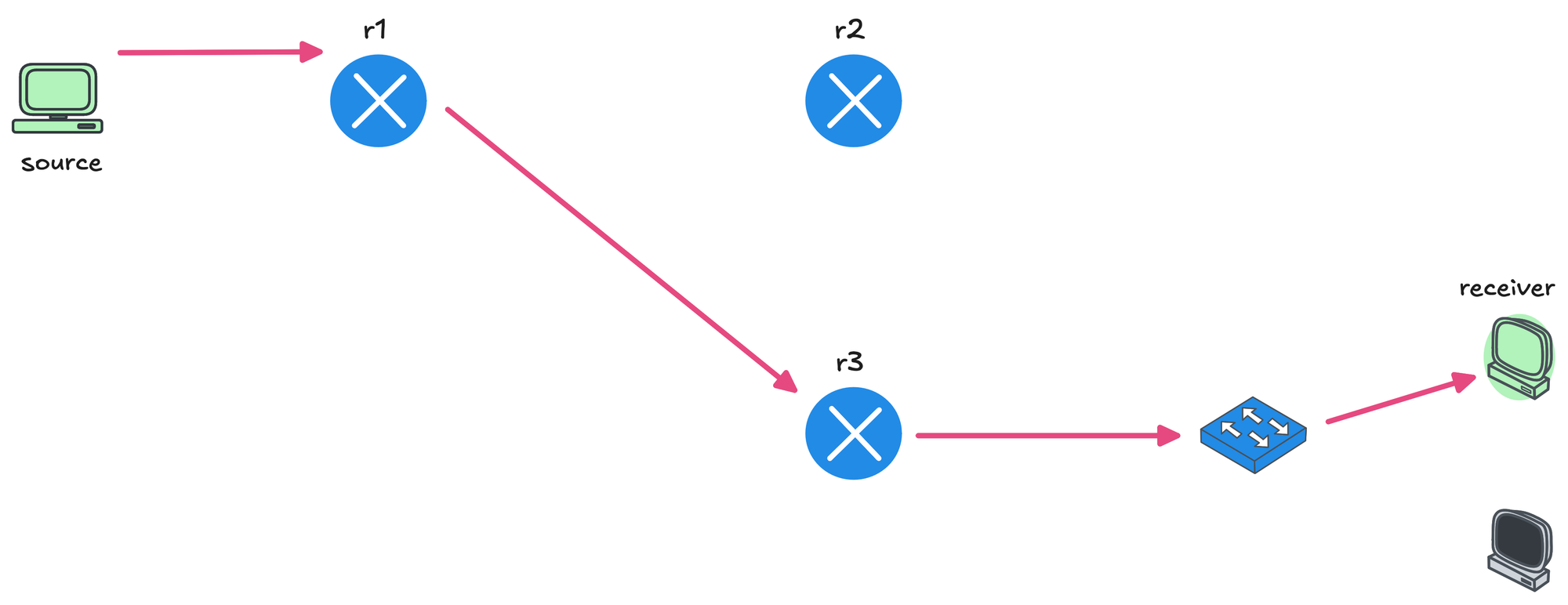

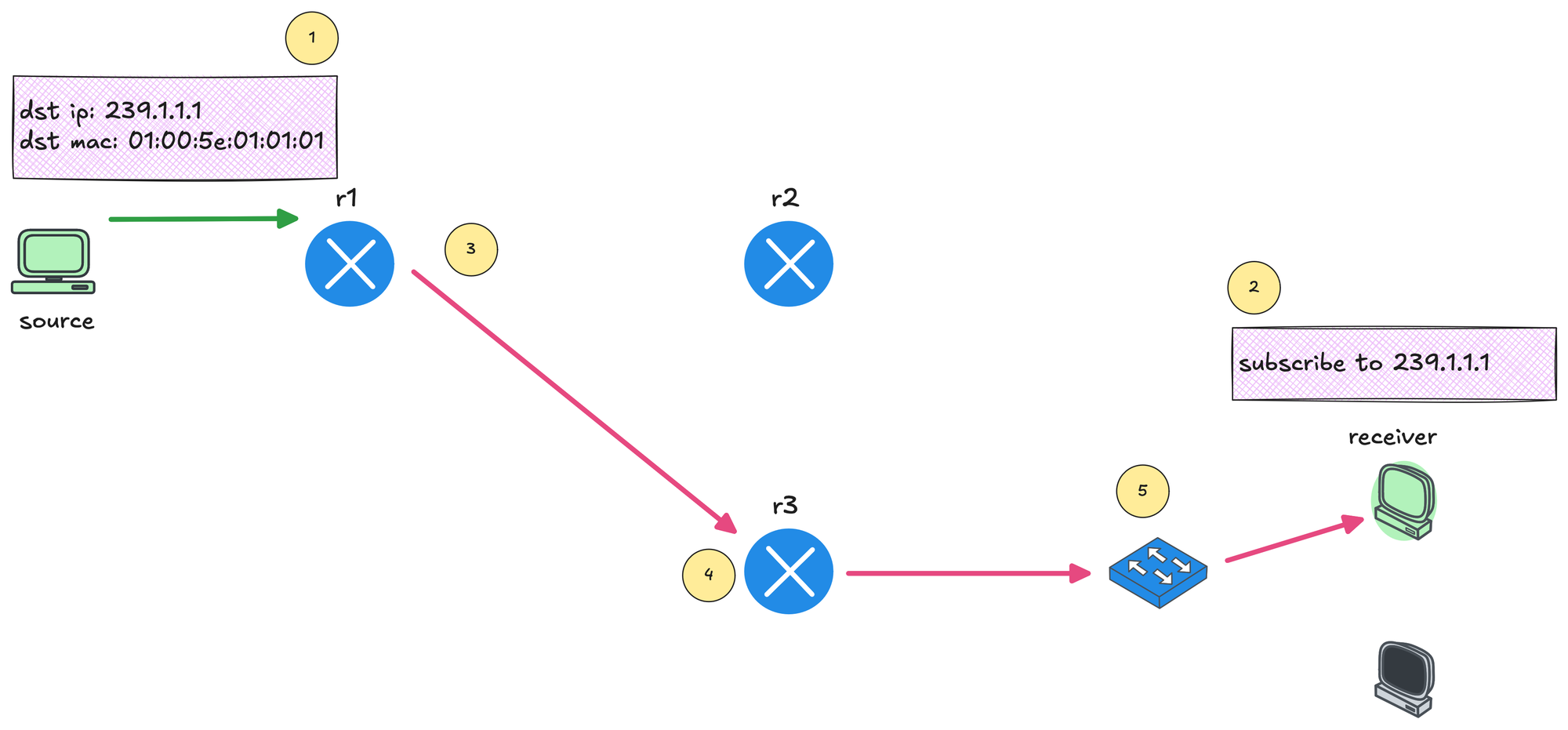

At a high level, multicast works like this. The source starts sending traffic to a multicast IP address, which represents a multicast group. Any number of receivers can choose to subscribe to that group. In this example, we only have a single receiver that wants the stream.

With help from various multicast protocols, a multicast-enabled network makes sure the traffic is only forwarded where it is actually needed. Routers learn where interested receivers are and only send the stream down those paths.

You can see that r1 forwards the multicast traffic toward r3 because there is an interested receiver behind it. At the same time, r1 does not forward the traffic toward r2, because there are no receivers on that side that have subscribed to the multicast group.

Remember, the source only ever sends a single copy of the multicast stream. The duplication happens inside the network. If r2 also had a receiver that subscribed to the same multicast group, r1 would replicate the traffic and forward one copy toward r3 and another copy toward r2. The source would still send just one stream.

Also, remember, the sender does not need to know the IP address of any receiver. It simply sends traffic to the multicast group address. Multicast traffic is also sent using UDP.

Multicast Reverse Path Forwarding (RPF)

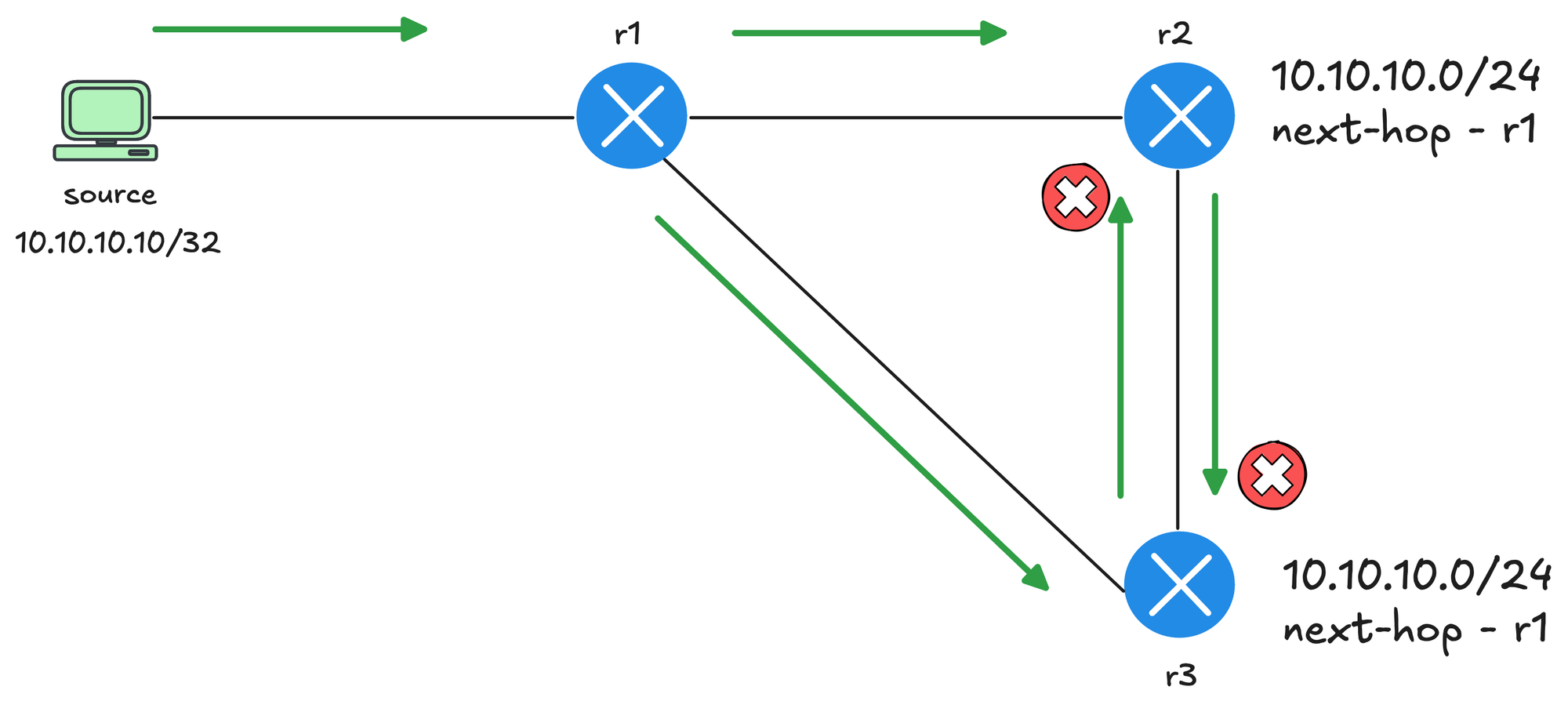

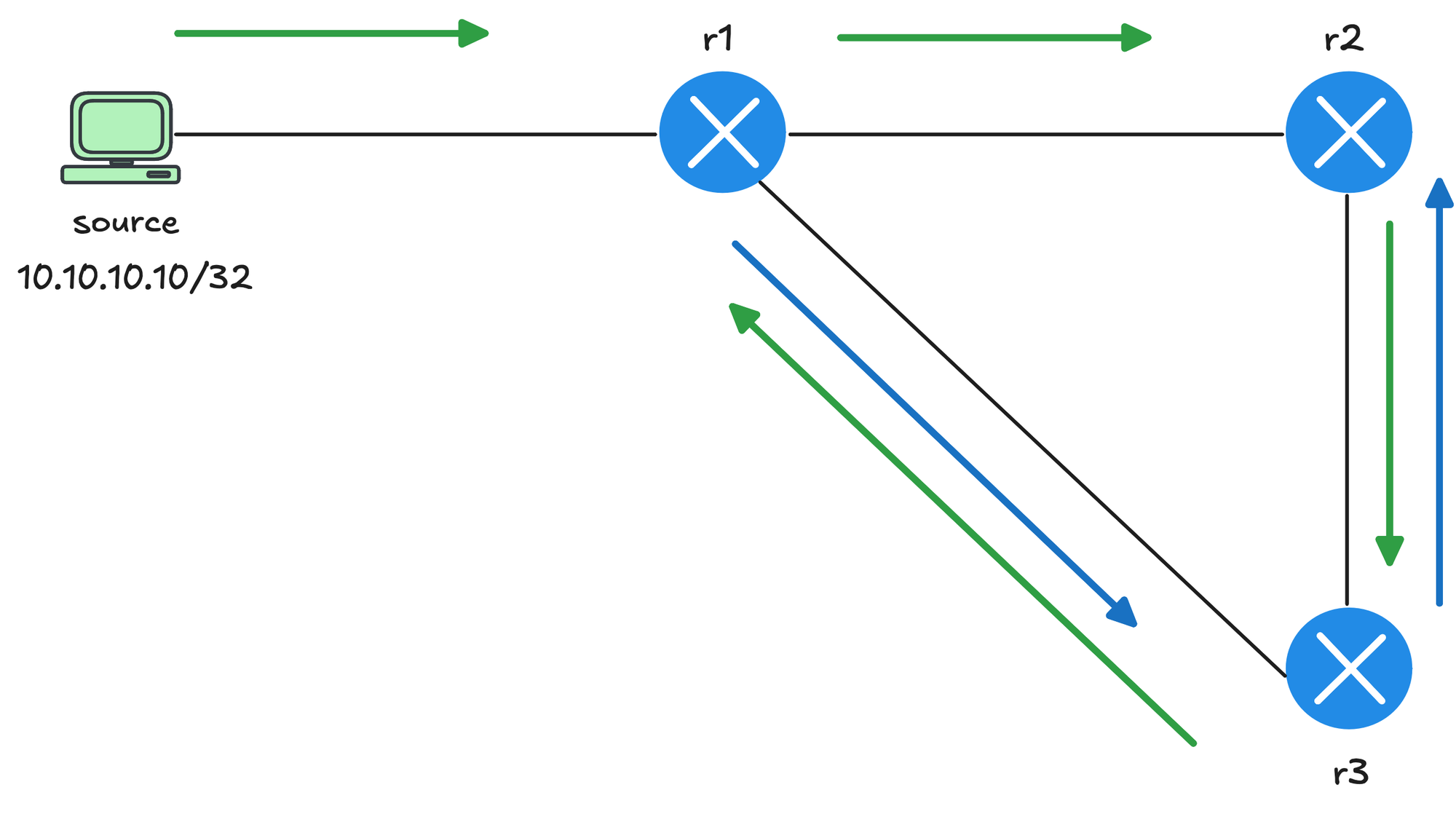

Before getting into RPF, it helps to understand the problem it is trying to solve. In this diagram, the source sends multicast traffic to r1. r1 forwards the traffic to r2 and also duplicates the packet and sends it to r3 (assuming there are interested receivers behind all three routers). So far, this looks reasonable.

The problem starts next. r2 forwards the multicast traffic down to r3. At the same time, r3 is also receiving the same multicast traffic directly from r1. Without any checks in place, r3 would then forward the packet it received from r2 back toward r1, creating a loop. This results in duplicate packets and unnecessary traffic flowing around the network, which is clearly not ideal.

With RPF, when a router receives a multicast packet, it checks the source IP address of that packet and looks it up in its unicast routing table. The router then asks a single question - Did this packet arrive on the interface I would normally use to reach the source? If the answer is yes, the RPF check passes, and the router is allowed to forward the multicast traffic. If the packet arrived on any other interface, the RPF check fails, and the packet is dropped.